“Café acuchawa, acuchawa, café manguana, acuchawa…”

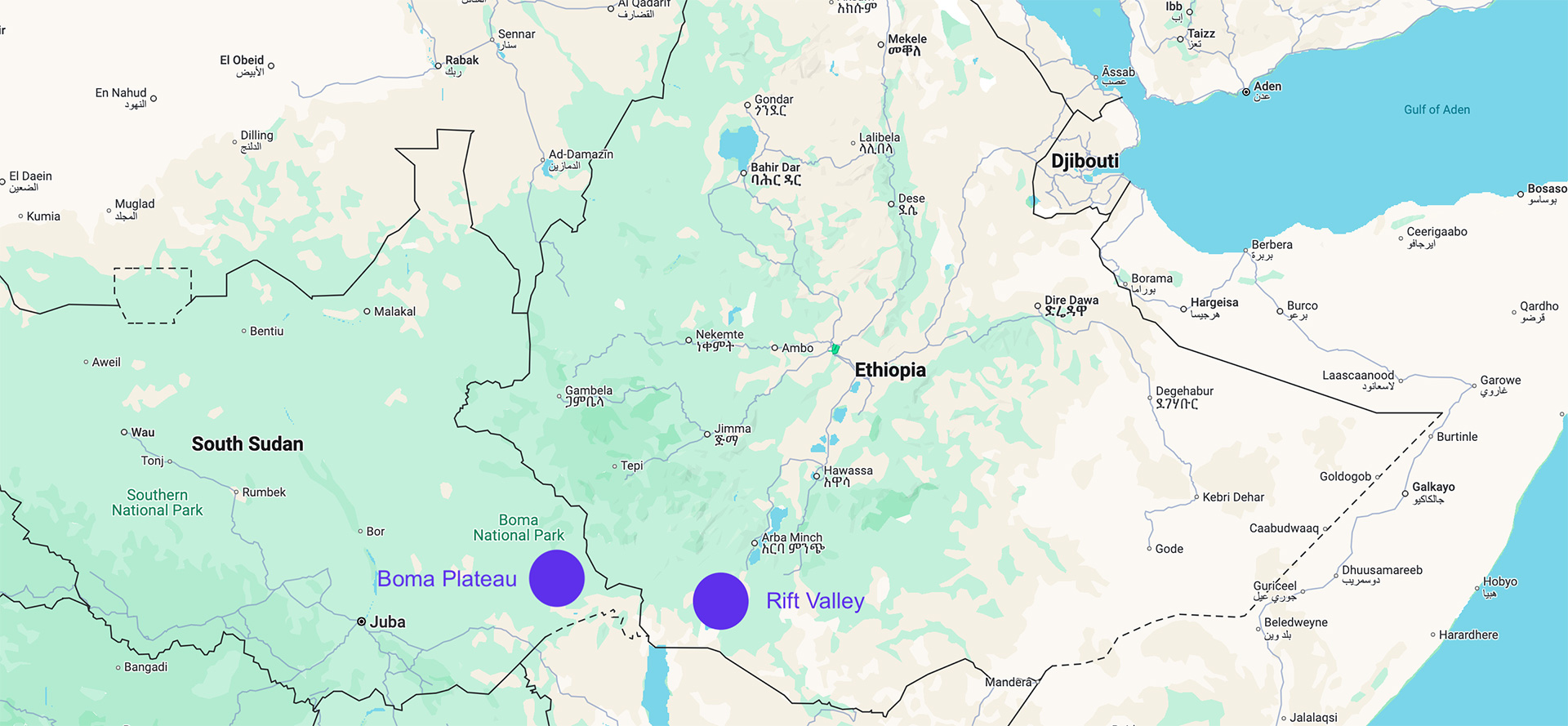

In Gorongosa, in the southern end of the Great African Rift Valley in the heart of central Mozambique, coffee farmers sing a song that melodiously translates to “coffee for a better future”.

Here on a mountain enrobed in rainforest, women walk into the forest in the mornings, not to fetch firewood, but to pick coffee. This crop—once foreign in these lands—now grows under ancient green canopies, helping reverse the degradation of ecosystems and creating a case of coffee bushes restoring a deforested mountain area that once teemed with many indigenous trees. In Mozambique we can find a real live experiment in the possibility and promise of community-supported agriculture in coffee.

Gorongosa Rainforest Restoration Project

The Gorongosa Restoration Project (GRP) is an initiative born two decades ago through a partnership between the Mozambican government and the Carr Foundation. I’m speaking today with Camille de Boissel, the Associate Director (Regenerative Agriculture Institute and Coffee Project) at Gorongosa, who tells me about the challenges this project has faced over the last ten years. Chief among them? “The presence of an opposition military base on Mount Gorongosa and widespread slash-and-burn farming practices in the park and its buffer zone,” says de Boissel.

The Gorongosa coffee project began in 2014–2015, and is a component of the GRP initiative. According to de Boissel, it was Pedro Muagura, the Park’s Warden and an expert in agriculture, forestry, and wildlife management, who proposed coffee cultivation as a solution to reforest the area. By planting native trees alongside coffee in an intercropping system, the initiative aimed to restore the forest by creating shade-grown coffee, and providing local communities with a sustainable income. Despite initial skepticism, Muagura procured some seeds and established a small nursery on Mount Gorongosa, marking the introduction of coffee—a crop previously unknown or tasted in the region.

From Few Bags to Shipping Containers

An agronomist Quentin Haarhoff helped to build the coffee project from 2014 to 2021. The first harvest in 2018, yielded only a few bags of coffee. In 2019, Camille de Boissel joined as a consultant to enhance the project’s quality, post-harvest processing, and traceability efforts. Over time, her role evolved into that of coffee manager, co-leading the initiative alongside Haarhoff.

When the project started, Mozambique’s coffee sector was almost non-existent, largely due to the devastating civil war lasting from 1977 to 1992 marking a prolonged period of economic decline. But today, the coffee project, co-led by Gary Dodd, has grown from producing a few bags of coffee to filling entire shipping containers. In the early days this work engaged fewer than a dozen farmers. Today it works with more than 1,000.

In addition to its agricultural efforts, Gorongosa Coffee Project was instrumental in the creation of the Mozambican Association of Coffee Growers (AMOCAFE), de Boissel tells me. “As a founding member, Gorongosa Coffee unified stakeholders across the coffee value chain, bringing together companies, producers, and industry advocates committed to growing and promoting coffee in Mozambique.”

The founders also established Produtos Naturais da Gorongosa (PdG) in 2019, a for-profit venture, managed by Sofia Molina (a key person for the project) that develops local and international coffee markets for Gorongosa Coffee and other products while re-investing all profits in the Gorongosa Restoration Project.

Coffee Arabica Under the Shade

The project grows Coffea Arabica under shade in an innovative agroforestry system. This system incorporates intercropping with pineapple, beans, and bananas in previously deforested areas environmentally suitable for coffee. This approach has a dual benefit. On one hand, this agroforestry model supports reforestation and biodiversity by incorporating native tree species contributing to the ecological health of Mount Gorongosa. On the other hand, the intercropping system enables farmers to diversify their crops, providing multiple income streams and fostering greater economic and climate resilience.

Introducing coffee as a new crop was a gradual process, as local farmers needed time to adapt to growing something they had never cultivated before. Progress was initially slowed in 2015-2016 due to political instability in the region and like in Rwanda’s Best Quality Coffee Project, a lack of initial knowledge about coffee cultivation among farmers.

“Today, the Gorongosa coffee project stands as a successful proof of concept,” de Boissel tells Sprudge Media. “What began with just five hectares has grown to over 200 hectares, with farmers across eight communities in three distinct areas of the mountain: Tambarara, Canda, and Sandundjira.”

The project’s long-term vision is to gradually reduce green bean exports while scaling up sales of the A Nossa Gorongosa brand both locally and internationally and dealing with fluctuations in coffee production and market prices.

Currently, the project processes over 40 tons of green beans annually. It has three wet mill stations (one in each production area) and a dry mill facility equipped with modern technology such as a cleaner, huller, grader, catador, and density table, along with African beds for drying and upcoming mechanical dryers. For the local brand, dedicated roasters and a packaging line ensure the coffee is ready to meet local market demands.

Shade-Grown Coffee to Conserve Wildlife

Mt. Gorongosa is home to over 1,500 species of animals and plants, surrounded by a belt of shade-grown coffee that protects the forest and helps reforest areas destroyed by slash-and-burn agricultural practices.

According to de Boissel, coffee plantations provide an alternative habitat for many forest animals in the region, including some found nowhere else. Research done at GRP has shown that eight-year-old coffee plots that provide habitat for 82 species of birds, spiders, and butterflies are 60% similar to the natural forest. These coffee plots are also good habitats for bats, including an endemic species, the Gorongosa horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus gorongosae). Additionally, birds visiting the coffee plots help disperse seeds of 51 species of native Mount Gorongosa rainforest trees.

Supporting Local Farmers

Gorongosa’s commitment to engaging local farmers, especially women in the coffee project has been a remarkable success, with nearly 50% of them being women. A particularly inspiring story is when during local conflicts in 2015-2016, when Canda faced significant instability and the coffee project was temporarily put on hold, a group of women would go to the nursery to irrigate the remaining seedlings, under the cover of the nights ensuring the survival of the young coffee plants.

As de Boissel tells us, the project also offers training to the local farmers and “provides seedlings, agricultural inputs, and seeds to bolster food security, alongside initiatives to promote financial inclusion (such as Village Savings and Loan Associations) and income diversification. GRP integrates its agricultural efforts with programs in education, health, and human development, ensuring a holistic approach to community development.”

Gorongosa Coffee Supply Chain

Each production area—Canda, Tambarara, and Sandundjira—has its wet mill, with processed coffee transported to Mapombwe in Vila Gorongosa for drying. After drying, the coffee is stored for about a month in jute bags before being processed into green beans.

As de Boissel explains, Produtos da Gorongosa handles the cherry coffee processing, focusing on fully washed and natural processes. Additionally, experimental post-harvest methods, such as anaerobic fermentation and honey processing, are also explored.

The project also features a state-of-the-art coffee lab and a local team with specialized training in green bean analysis, cupping, and the evaluation of organoleptic qualities. This year, approximately 346,000 kilograms of cherry coffee were processed but due to the challenges posed by climate change, 90% of the coffee was processed as fully washed to preserve its quality and mitigate risks linked to post-harvest practices.

GRP also has a science department that helps the project understand and measure the impact of the coffee initiative on biodiversity and ecosystems. The department also conducts surveys in coffee plantations, providing detailed species data, thus leading to a better understanding of potential species that could become pests.

Looking Ahead

Mozambique has over 15 active coffee initiatives, a National Coffee Strategy Plan, and has ascended to the International Coffee Organization (ICO). The coffee sector goes beyond Coffea Arabica to include C. Robusta, C. Racemosa, and C. Zanguebariae. By capitalizing on Mozambique’s unique coffee species and scaling production strategically, the country is well-positioned to establish itself as a key player in regional and international coffee markets.

“The vision for Gorongosa coffee is undeniably ambitious,” de Boissel says. She has big goals for the project, including a dream of someday seeing Mozambican coffees roasted by the world’s best specialty coffee companies and served at fine cafes. “To see…the Gorongosa logo and brand, and perhaps a description noting that this coffee is free of deforestation and bat-friendly among other attributes….such recognition would symbolize the culmination of efforts to showcase the unique attributes of this coffee and its positive impact on the environment and local communities.”

Daniel Muraga is an anthropologist and freelance journalist based in Nairobi