When a person with a passion and a dream taps into the power of coffee, the results can be awe-inspiring. Dennis De Wet has turned his dream into Namibia’s most beloved coffee brand with his innovative Slowtown Coffee Roasters. When this coffee entrepreneur was collecting and selling empty bottles at a local corner shop just before starting university, no one would have imagined he would establish a brand that now supplies coffee to some of the biggest hotels, restaurants, lodges, offices, and other establishments. Although Namibia is home to the Namib—the oldest desert in the world—and is considered one of the driest and most sparsely populated countries on the planet, De Wet has expanded his coffee business to more than seven stores. Can it get even more puzzling? Namibia produces no coffee.

Slowtown was born back in 2011. At the time, De Wet tells Sprudge Media he was working in finance, doing the whole corporate thing after studying Financial Analysis at Stellenbosch in South Africa. He found the corporate world unfulfilling and started realizing he wanted to build something more meaningful, that aligned with the things he cared about. Among the things dear to his heart were surfing, Grand Prix, wine, food, and coffee.

“Coffee had always been a passion, but more than that, I loved the idea of creating a space where people could slow down and connect with themselves, and with a great cup of coffee,” De Wet tells us. “That’s where the name Slowtown came from referencing not just a coffee brand but also a mindset. We even chose a snail as our logo to remind people to take things slow.”

Coffee Background in Namibia

You might be familiar with the Kalahari Bushmen, or the Namibian N!xao, who starred as the lead actor in the 1980 movie, The Gods Must Be Crazy. These depictions of Namibia hardly evoke the lush green rolling hills of the coffee farm.

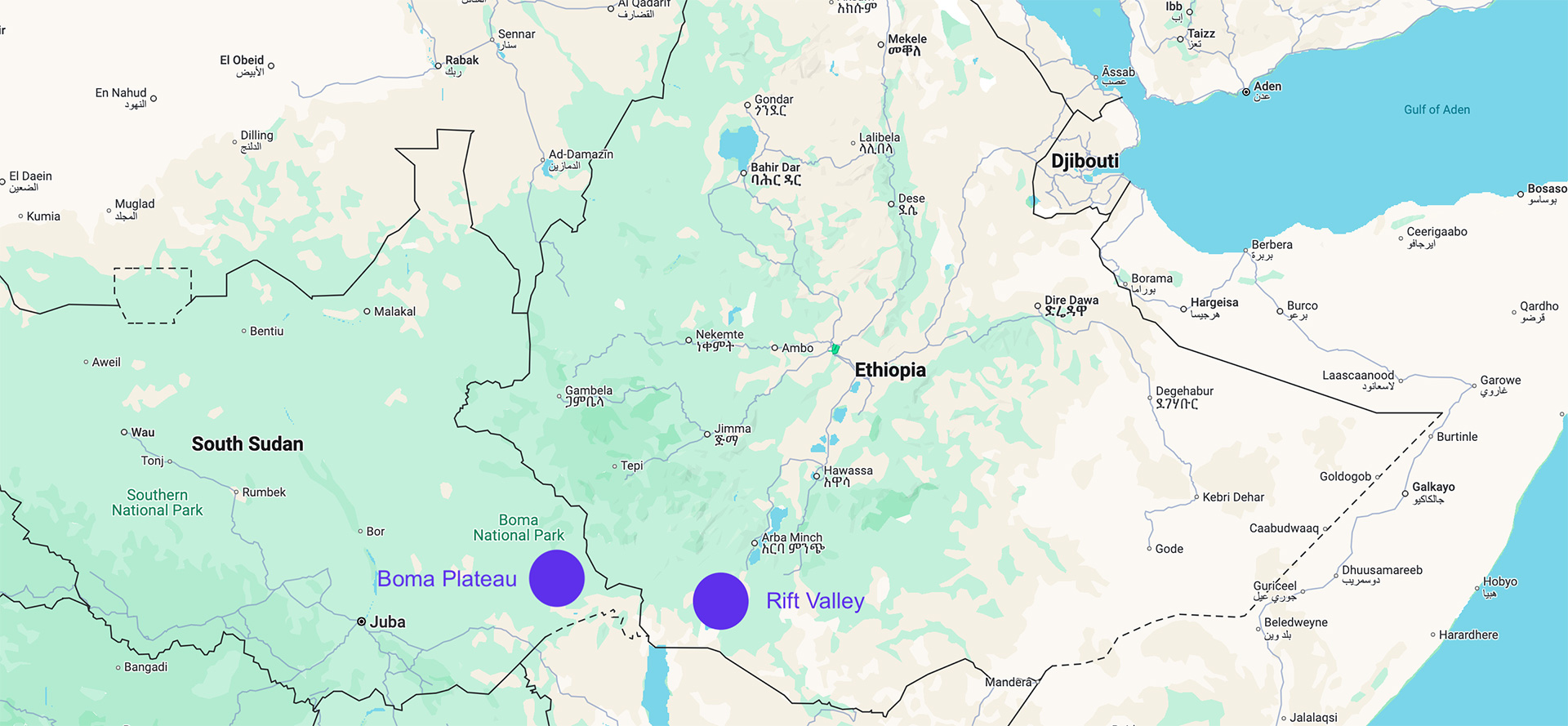

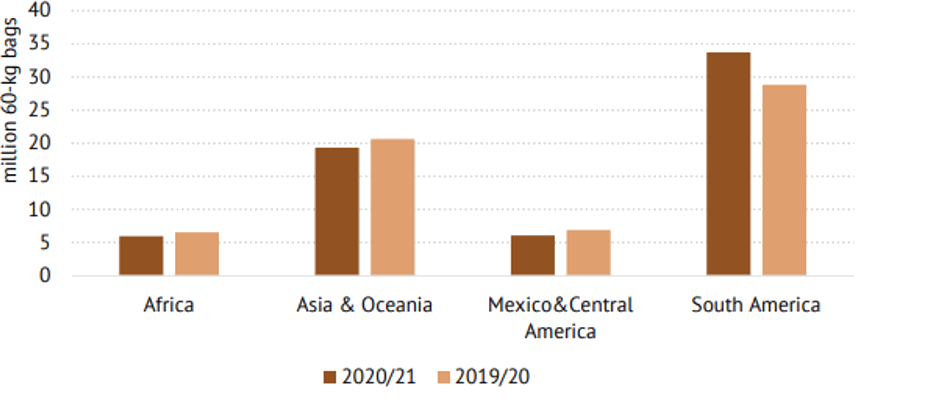

Simply put, Namibia does not have a local coffee farming industry, because the country’s climate, soil, and geography do not favor coffee growing. However, it has a thriving coffee roasting scene and a rich consumption culture. Coffee roasters are strategically located in major cities (including Windhoek, Swakopmund, and Walvis Bay), where coffee shops and cafes are becoming increasingly popular. Unlike on the fertile eastern side in countries such as Mozambique, coffee is imported from other countries in Africa, South and Central America.

Namibia is on the newest countries in the world; though inhabited for thousands of years by the Khoi, San, and Nama peoples (and the Bantu and Ovambo, who arrived in the 15th century), the modern nation state gained independence in 1990, after a period of border wars and shared administration by the United Nations and South Africa. When visiting Namibia’s cities you’ll see vestiges of the former German colonial rule, a brief tenure marked by conflict and violence. Namibia is also one of the most sparesely populated countries in the world, behind only Australia and Mongolia; just three million people live within its borders, despite the country being larger than the state of Texas.

Slowtown Coffee began with a small shop in Swakopmund (a city on the western coast), roasting in small batches and serving the community. Since then, it has grown organically. The company has opened additional locations in places like Windhoek and Walvis Bay, and it has developed a strong wholesale segment of the business. Now it supplies coffee to lodges, offices, and restaurants, and assists others in setting up their coffee stations. They also operate a barista training program to maintain consistent quality wherever their coffee is served.

Slowtown’s focus is firmly on specialty coffee. “We offer a range of single-origin coffees and blends, but what ties everything together is our commitment to balance, clarity, and smoothness in the cup,” Geena Prior, the Marketing Manager at Slowtown Coffee tells us. “We’re not big on overly dark or bitter roasts—that’s just not our style. We want our customers to taste the bean, not the burn.” This might mean offering fruity, bright coffees hailing from Ethiopia, or washed coffees with a rich complexity from Central America. Slowtown’s roasting style should be familiar to readers who enjoy specialty coffee elsewhere in the world: clean, nuanced, approachable and never burnt.

Hands-on Process from Farm to the Final Pour

Slowtown Coffee offers everything from espresso to pour-overs, with their blends designed versatile enough to work just as beautifully in a flat white as in a traditional Americano. And their process from source to cup is hands-on. According to De Wet, the company aims to ensure that every step, from the farm to the final pour, reflects the quality and care that define its brand. In the sourcing stage, they work closely with a trusted broker based in South Africa who helps them connect with producers worldwide, primarily from Africa, Central America, and South America. Once the green beans arrive, they are roasted in Swakopmund, a small city on the western coast of the country where the company began.

The company takes full control over the process and fine-tunes each roast profile by roasting in small batches. After roasting, the coffee is either sent out to shops or delivered to wholesale partners. Once the roasted coffee reaches the company cafes, trained baristas treat each cup with as much care as they do during roasting, paying attention to every detail from espresso calibration to milk texture. If the roast goes to a lodge, cafe, restaurant, or office, they offer support and training so that these consumers can make the most of the beans.

“We take our time with every step to ensure we’re doing justice to the coffee and creating a moment of pause and enjoyment in every cup,” De Wet says.

Challenges

Slowtown has had its fair share of challenges, like any other business, especially one that’s a bit niche-focused. She identifies introducing and growing the culture of specialty coffee in Namibia as one of the biggest issues they face.

“When we started [2011], most people in Namibia didn’t know what single-origin coffee was, or why small-batch roasting mattered,” she tells me. “There wasn’t a big coffee culture yet, not in the way we saw in places like Cape Town or abroad. So a lot of it was about education: talking to customers, tastings, showing them that coffee can be more than just something you grab on the go.”

As noted earlier, Namibia does not grow coffee, so everything the company roasts is imported. This creates logistics and supply challenges. Consequently, the company consistently faces shipping delays, customs processes, and unpredictability from relying on international supply chains. To address this, the company has established strong relationships with suppliers and the broker in South Africa, and typically plans ahead.

Then there is the general challenge of running a business in a small economy like Namibia, where growth takes time, and where decisions on where and how to expand require expertise “We’ve leaned into building a loyal customer base,” De Wet says, “ensuring every shop delivers on the Slowtown experience. Word of mouth has been huge for us and every challenge has pushed us to be more creative, focused, and grounded in our values.”

Looking Ahead

Namibia is a country with challenges, but also a place where it’s easy to feel optimistic about the future, and Slowtown reflects this in their work as Namibia’s leading specialty coffee brand. The company is all set and excited about expanding and spreading its wings in Africa and beyond, with future goals that should sound familiar to anyone wiht a growing coffee business.

“We’ve built up our roasting capacity and we’re looking into new markets in places like South Africa, and potentially online into Europe,” De Wet tells me. “But through it all, the heart of Slowtown stays the same: make excellent coffee, and create those little moments of pause that we all need in a busy world.”

Daniel Muraga is an anthropologist and freelance journalist based in Nairobi.