Switzerland is not only famous for its mesmeric alpine sceneries. For coffee lovers, popular coffee shops beckon, like Mame in Zurich, Sleepy Bear in Lausanne, and Boréal in Geneva. It is also home to the coffee-loving tennis world champion Roger Federer (who takes “three to four” coffees a day, enjoying cappuccino in the morning, an espresso after a meal, and occasionally a ristretto just to mix things up). Despite being a relatively small, landlocked country, far away from key trading routes and major ports, it is a leader in transit trading for coffee (and other major commodities such as sugar, grains, crude oil, and metals). Switzerland and other countries in Europe lead the world in global commodities trade despite lacking the climatic conditions necessary to grow most of those very commodities. Europe has built a massively profitable export system through hundreds of years of import and re-export of raw commodities from Africa and other countries in the global south, coffee chief among them. But a new generation of African leaders and coffee producers are calling for change—and what comes next will write a new chapter in the centuries-old coffee trade.

Coffee As A Global Market: A Brief Background

According to an International Coffee Organization (ICO) report, European re-exporting countries earned an average of over $300 per standard bag of coffee exported between 2000 and 2010. Meanwhile, their counterparts in Africa and the rest of the global south earn around $106 per bag, or roughly 1/3rd the total earnings. This is despite the fact that many African countries still rely on foreign exchange for economic development.

Studies show that African nations lose some £8 billion a year from irregularities in commodity trading prices with Switzerland alone. And the Swiss model is not alone; these figures do not include other European commodity re-exporters such as Germany, Belgium, France, Italy, and the United Kingdom.

According to ICO, European countries earn over three times higher from the export of coffee products than countries in Africa. But is it because of value addition? I asked this question of Tedd George, an expert in African markets and commodity value chains and Founder and Chief Narrative Officer at Kleos Advisory Ltd. “The key imbalance in Africa’s coffee trade with the world is the fact that Africa is exporting most of its beans raw and capturing only a small part of their value,” George told me. “The global industry is set up in a way that incentivizes Africa to export its beans raw and this needs to change,” he says, adding that “it’s all about value addition. Africa gets only the price for its raw beans, while in Europe the beans are roasted, packaged, and sold as coffee in cafes. This pushes all of the value addition to the end of the value chain, excluding Africa. The key for Africa is to develop more local roasting and packaging, but also local demand for coffee.”

George’s point is backed up by numbers. According to a report by International Trade Centre, more than 90% of coffee around the world is exported as raw or “green” beans, owing to coffee’s long history as an export crop. Despite annual international demand for coffee rising by 2%, most smallholder coffee farmers in Africa are languishing in abject poverty. Take, for example, the nation of Kenya, home to some of the most desirable coffee in the world, sought after by coffee roasters all across the planet. Here in Kenya, there are more than 700,000 smallholder farmers, and many of them operate at a loss. And that’s not just here: around the world there are millions of other coffee farmers who struggle to earn a living wage. The coffee supply chain is driven by buyers, and statistics show they capture the vast majority of the profits. What of the farmers?

Understanding the Value-Addition Problem

Samuel Mwithukia Kimani is the Director of Kimani Coffee Experts Ltd, a company that buys, processes, and sells Kenyan coffee locally and to the Far East, Europe, and the USA. Kimani has a unique perspective on the issue of value-addition and is actively working to address the systemic problems facing Kenya’s coffee farmers. “Lack of value addition in coffee—exporting it in raw form along with political and economic instabilities—are factors that put many African coffee-producing countries at a disadvantage at the global market level,” Kimani tells me. “To make the matters worse, many African countries deposit their money in Switzerland. There is cheap money in Switzerland but little or nothing for African farmers.”

Coffee value-addition is touted as one of the main reasons why European countries fetch more profits than their African counterparts. There’s good reason for this, and it’s quite troubling. “You can only get so much value from a raw coffee bean,” says Tedd George of Kleos Advisory. “As soon as you process it, the value addition starts.” It stands to reason, then, that African countries can become more internationally competitive in advanced coffee processing activities by focusing on adding value first at home. If only it were that easy.

Value-Addition Flaws

“Coffee roasting and packaging is complex,” says George, “and requires cheap and efficient energy, which is not always available in Africa. Africa is unlikely to be able to compete with South America and South-East Asia when it comes to producing bulk coffee, but with specialty brands, it could produce competitive packaged coffee for the world market.”

But according to Angus Elsby, this value-addition narrative is flawed. It assumes the value in final cup taken in coffee joints in Europe is solely derived from better retailing, marketing, and use of more advanced processing methods, like roasting or decaffeinating. This ignores preexistent trade imbalances where global commodity market policies favor European countries. The trend has been the concentration of very large coffee traders leading to monopoly capitalism. Over time, these big multinationals have merged, while enjoying weak, little, or no anti-monopolization laws in home countries, to create even more powerful coffee re-exporting empires setting the bar too high for African coffee farmers.

In addition, the environmental and social costs of coffee production in Africa are usually ignored in the global coffee pricing system. Proper pricing should, as noted by experts, incorporate in the overall cost of coffee, the burden that coffee farming places on society. This includes issues like water and soil pollution, farmers and worker’s social and economic security, as well as a proper living wage. Historically and unfortunately this has not been the case in Kenya, or across the rest of Africa. What comes next is change, and there is no change without a fight—a fight for Africa to earn what it deserves from the global coffee trade.

One Step Forward, One Step Back

Coffee cooperatives in Africa are crucial in buying, setting prices, controlling quality, negotiating prices with global traders, and coordinating coffee auctions. Some cooperatives in nations like Rwanda, Kenya, and Burundi have even become well-known to international specialty coffee consumers, appearing on bags of coffee as trusted purveyors of some of the world’s most delicious coffee. However, following trade restructuring that started in the 1990s, many cooperatives have been dismantled across Africa. This has left the continent with little or no collective bargain in the global commodity market.

Low prices, too much unpredictability, and poor yields (due to changes in climate) not only affect farmers’ revenue, but also decreases interest of present and future farmers in coffee farming. It also causes labor shortages during coffee harvesting time.

“Part of the problem is that Africa is a small player when it comes to global coffee flows,” explains George. “50 years ago when Angola was one of the world’s largest coffee producers, volumes were much lower and Vietnam didn’t even export coffee. Today Brazil and Vietnam account for the vast majority of Arabica and Robusta production and exports, giving other producers in Africa little pricing power,” George explains.

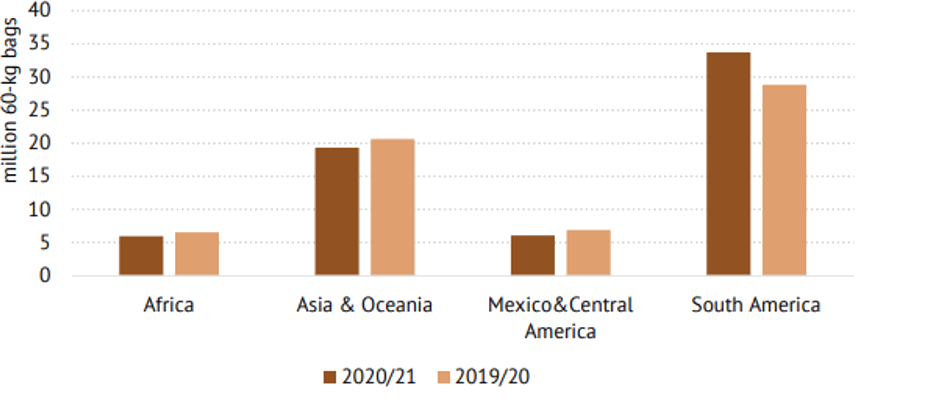

According to the ICO report, exports of all forms of coffee from Africa in the first half of the coffee year 2020/21 reduced by 8.9% to 5.96 million bags. Exports from Ethiopia, Côte d’Ivoire, and Kenya dropped by 28.5%, 49%, and 9.5% respectively.

Trade imbalance against Africa, along with other contributing factors, has resulted in this fall-off in production. What’s left is an open question: how does African coffee survive when the deck is stacked against it?

Looking Ahead

A diverse pool of experts with various interests agree: in order to get the most out of coffee, the key for Africa is to boost local value addition and consumption, and to develop a robust economy of local specialty brands. Africa has been afforded no real pricing power on the international commodities market, which is flooded with bulk beans; there is a glimmer of hope in the international consumption of high quality, high scoring coffees beloved by Sprudge readers, but this represents but a fraction of total coffee production. In order to impact change in Africa we must address the entire market—not just specialty. But a growing interest in coffee at home, in Africa, offers a path forward.

“The key to getting more value from African coffee is boosting local demand,” agrees George. This shifts the paradigm, making it so producers are not entirely beholden on the export market for their crop. Ethiopia offers an intriguing case study, adds George. “Ethiopia consumes half of its own Arabica production, consequently commanding pricing power for its exports, notably that of Yirgacheffe coffee which commands a high premium, while its neighbor Uganda consumes little of the Robusta it produces and consequently gets a poor price for it.”

The same sentiments reverberated in the words of Mr. Kimani:

“You cannot compare a well processed, packaged, and finished product with raw materials in terms of marketability. We [Africa] should export our coffee in finished form because by exporting in raw form, we are also creating employment in Europe at our disadvantage. We should design our own attractive packaging materials for global competitiveness. We should improve our coffee consuming culture locally thereby improving the local market for coffee.”

How can Africa get a better cup of coffee in the global arena? The answer is promising: domestic consumption and the development of ascendent African coffee brands offers a broad range of benefits for the continent’s coffee farmers. One early leader on this front is the brand African Coffee Roasters. Located in the Export Processing Zone (EPZ) in Athi River, in Keya, ACR was established in 2015 and serves as a perfect case of local coffee processing in Africa.

Among its products include “The Big Five” brand that contains five different single-origin coffees from five different coffee cooperatives in Kenya, Ethiopia, Rwanda, DR Congo, and Uganda. In addition to the value-added at the coffee processing level, the company also sources nearly all of its packaging materials from local suppliers, including laminate material for the pouches, cardboard among others. ACR boasts of a state-of-the-art roasting and packaging facility including two Loring 70kg Peregrine coffee roasters, two form-fill-seal packaging machines, a compostable Nespresso capsule packaging line, a hand-packing line, a fully equipped Quality Control Laboratory, and a nitrogen generator. This equipment is especially important, says Stephen Vick, the Head of Coffee at ACR. “The Loring roasting technology allows for unparalleled control on our roast profiles,” says Vick. “These machines are only four in Africa: our two, one in Kampala and one in Cape Town. In addition to this, our company and facility carry a number of certifications: FSSC 22000 (highest global food safety standard), EU Organic, Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance/UTZ, SMETA, BSCA, and we are a member of the UN Global Compact,” adding that the future of local coffee production and consumption in Africa is bright “I’ve seen tremendous change in both local processing for export as well as local consumption thanks to brands like Spring Valley Coffee, Connect Coffee, Barista and Co. and others. As the entire hospitality industry in East Africa is dynamically developing (restaurants, beer, wine, cocktails, boutique hotels, etc.), I see coffee naturally following suit.”

Rather than compete with the bulk coffee market—which experts like Tedd George feel is all but impossible—Africa is poised to capture a larger share of the high-end global coffee market. This approach could serve to reduce power imbalances, according to Samuel Kimani. International markets can support this by championing African coffees as special, valuable, and highly sought-after, beautiful examples of coffee’s potential as a culinary wonder. Meanwhile, domestic consumption creates a daisy chain of opportunity for Africans in and around the coffee trade, from cafe owners and entrepreneurs to baristas, hospitality professionals, roasters, and all the way back to the farmers. Governments can also play a role, according to Mr. Kimani, who puts it bluntly: “African governments should be more involved in coffee production and research. Give farmers incentives to produce more.”

The future for African coffee is bright, and it starts right here, at home, in Africa.

Daniel Muraga is an anthropologist and freelance journalist based in Nairobi. Read more Daniel Muraga for Sprudge.