Between 1.08 million and 543 thousand years ago, deep in the montane forests of Ethiopia, a remarkable natural hybridization occurred. Two coffee species—C. canephora and C. eugenioides—came together, giving rise to the very first C. arabica tree.

However, this ancient tree was different from the C. arabica we know today. As both its “parents” were diploid species (meaning they carried two sets of chromosomes), the first C. arabica was also diploid. Then, somewhere between 10,000and 665,000 years ago, something called an polyploidization event happened, in which it caused C. arabica to double its chromosomes, making it the only one with four sets of chromosomes among over 130 discovered species of Coffea genus. (In case you wonder, “poly” means “many” in Ancient Greek, while “-ploid” basically denotes chromosomes sets in a cell). C. arabica is also one of just three Coffea species which are capable of self-pollination, alongside C. anthonyi and C. heterocalyx.

To us humans, these events may seem ancient, but in evolutionary terms, they’re surprisingly recent. As a result, C. arabica inherited incredibly low genetic diversity—the lowest among all species in the Coffea genus and the lowest among cultivated crops (in fact, comparable only to bread wheat). This limited diversity became even more pronounced as C. arabica began spreading across the globe roughly 600 years ago, starting in Yemen.

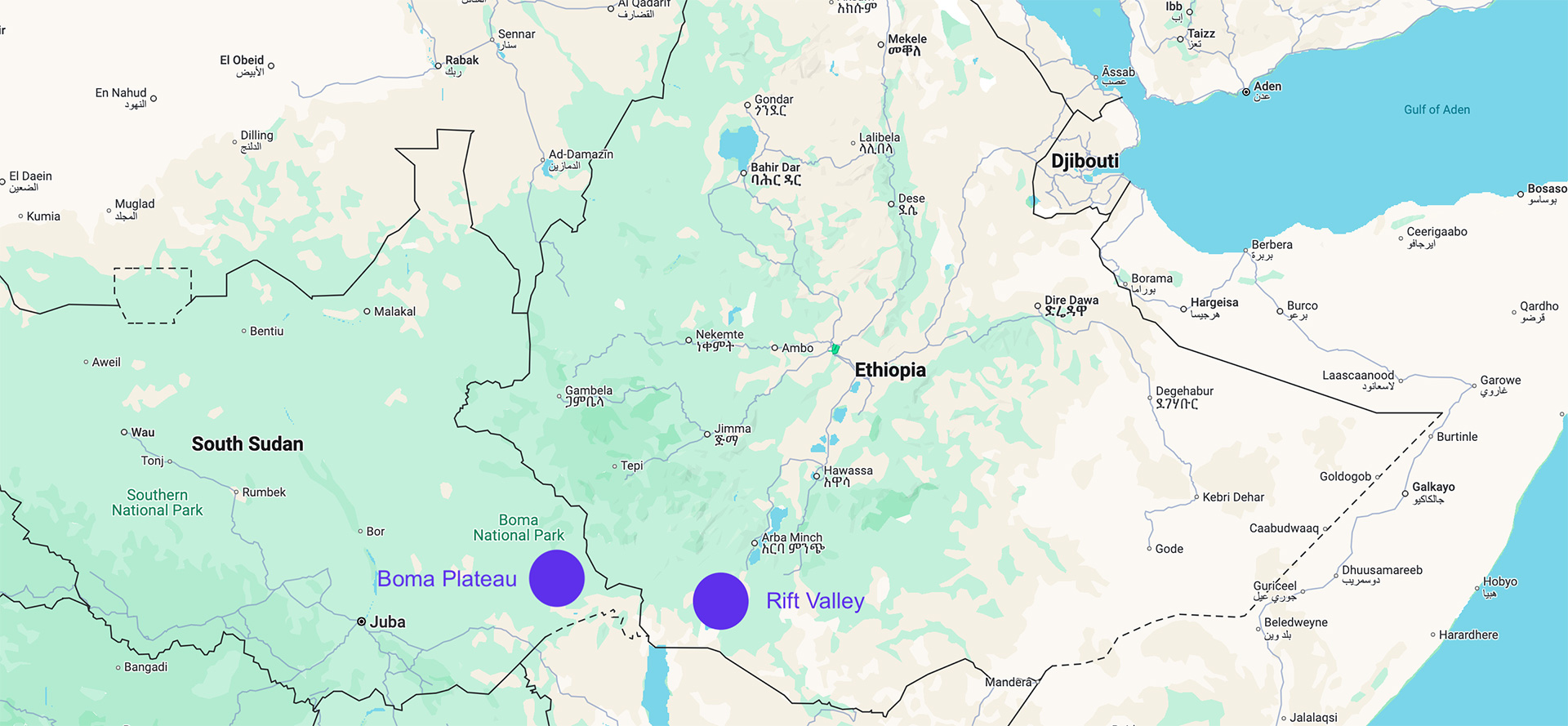

Recent research has pinpointed the southern part of Ethiopia, around the Rift Valley, as the original home of C. arabica. It also highlights the Boma Plateau in South Sudan as another key region of origin. If you’re a coffee aficionado, you might recall the Sudan Rume variety, which burst onto the specialty coffee scene in 2015 and is now widely grown in Colombia. Interestingly, coffee from South Sudan shows distinct genetic differences compared to its Ethiopian counterparts. Unfortunately, the genetic diversity of C. arabica native to South Sudan is under threat due to human activity, and likely climate change.

Out of Africa

The first instance of Arabica leaving its native home in Ethiopia is believed to have occurred in the 14th or 15th century—though the exact timing remains unclear. What’s really important, though, is that only a handful of Arabica seeds was transported from Ethiopia to the ports of Mokha in Yemen. This marked the first recorded movement of Arabica beyond its birthplace. However, the limited quantity of coffee exported from Ethiopia also triggered a significant reduction in genetic diversity, a phenomenon geneticists refer to as a “genetic bottleneck.”

Imagine a wild population of thousands of Arabica trees, each with its own unique traits. Now, take just a few of those trees and leave the rest behind—by doing so, you’re unintentionally selecting only a narrow set of characteristics, while the rest go into oblivion. This is essentially what happened, and as a result, much of the Arabica population cultivated today originates from that small, initial selection of genetic pool.

Yemen became the first country to cultivate Arabica, and it was confined in Yemen for the next two centuries. From there, coffee embarked on three primary routes to the rest of the world:

- The Yemen–India route

- The Yemen–Bourbon Island (now La Réunion island) route

- The “Escapee” route, where certain Ethiopian landraces spread globally without passing through Yemen.

The first two routes led to the development of the iconic Bourbon and Typica varieties, which are the genetic ancestors of many modern coffee varieties.

Yemen-India route and the rise of Typica

As a highly valuable commodity, coffee was tightly controlled in Yemen, with only roasted beans allowed to leave the country. Smuggling coffee seeds was considered illegal. Only until 1670, when an Indian Sufi named Baba Budan, who determined to grow coffee in India, famously smuggled seven coffee seeds out of Yemen—as the number seven is considered sacred in Islam.

What follows may sound like a bit of a history lesson, so please bear with me. Between 1696 and 1700, the Dutch East India Company transported coffee seeds from the Malabar Coast in India to Java in Indonesia. Just six years later, in 1706, a coffee plant made its way to Amsterdam, where it eventually bore fruit. Amsterdam’s mayor, Nicolaas Witsen, later gifted one of the plant’s offspring to King Louis XIV of France for his birthday, a tree that became famously known as the “Noble Tree”.

Fast forward to either 1720 or 1723, when King Louis XIV tasked French naval officer Gabriel Mathieu de Clieu with transporting coffee plants to the Caribbean. De Clieu succeeded, and soon coffee was spreading across Latin America, marking the beginning of large-scale coffee production in the region. These plants were believed to be of the Typica variety, which remains one of the most significant coffee lineages in cultivation today.

Yemen-Bourbon Island route and the Bourbon variety

Like Typica, the Bourbon variety also has its origins in Yemen but followed a different journey. In 1715, the French transported coffee seeds from Yemen to the island then known as Bourbon (named after the French royal dynasty), now called La Réunion. This is how the variety earned its name. For over a century, Bourbon remained on the island until it was finally brought to Brazil around 1850, from where it spread throughout Latin America.

From the 1940s, Bourbon began replacing the dominant Typica variety in Latin America, primarily because it was more vigorous and productive. Some traces of Typica still remained, like in Peru, or Jamaica, where the famous Blue Mountain coffee is in fact of Typica variety.

After its arrival in Brazil, Bourbon also underwent some significant genetic mutations, most notably the dwarf mutation, which was discovered around 1915–1918. This mutation gave rise to Caturra, a compact, high-yielding variety, which proved to be a game changer, since it allowed for more intensive coffee farming in full sun. Caturra quickly became one of the most economically important coffee varieties in Central America in the decades that followed.

Unfortunately, similar to Typica, Bourbon is highly susceptible to coffee leaf rust, which has wreaked havoc across Latin America over the past decade.

The escaped Ethiopian landraces

In addition to the two main routes (Yemen-India and Yemen-Bourbon), there were instances where coffee bypassed Yemen altogether, making its way directly from Ethiopia to other parts of the world. One of the most famous examples is the Gesha variety, which was brought from Ethiopia to Kenya in 1931, then to Tanzania, to Costa Rica before landed up in Panama. Another example is the Java variety, which first traveled to Indonesia before being introduced to Cameroon, where it was selected for its partial tolerance to coffee berry disease. The recent surge in popularity of Chiroso or Pink Bourbon is yet another case of these escaped varieties gaining recognition.

With genetic testing becoming more accessible, thanks to organizations like World Coffee Research, I believe we’ll soon uncover even more varieties that have followed this “escapee” route.

As globalization accelerates, unconventional varieties are popping up in unexpected regions like Latin America, China, and Taiwan. Personally, I’ve come across SL34 and Gesha in Taiwan— varieties traditionally associated with Kenya and Panama, respectively. The movement of coffee varieties across the globe is becoming so rapid and widespread that it’s getting harder to track these shifts—unless, of course, someone is diligent enough to document every step of this coffee journey.

What is next?

In a world where Arabica faces mounting challenges, discoveries about the new coffee varieties might offer a beacon of hope. The species itself is relatively recent, with an incredibly limited gene pool. The lower a crop’s genetic diversity, the more vulnerable it becomes to extinction, as we’ve seen with the Irish Lumper potato and the Gros Michel banana. In fact, by 2050, the land currently suitable for growing arabica could be reduced by half. This is on top of the existing threats like coffee leaf rust and coffee berry borer, which are already putting pressure on global coffee production.

However, the discovery of new coffee varieties with desirable traits showing that there are still untapped resources that could help secure Arabica future. These findings can aid scientists in breeding more resilient coffee plants. This represents a future of possibility for coffee—and coffee lovers—all around the world.

Tung Nguyen is the founder of Citric Meets Malic and a Sprudge contributor based in Hanoi, Vietnam. Read more Tung Nguyen for Sprudge.