Ukraine is the biggest country in Europe. It has a fast-growing coffee shop market, a world champion barista in the Cezve/Ibrik discipline and a world championship-winning roastery. Coffee culture is on an incredible rise here, this despite the now 10-year-old ongoing conflict with Russia. And now Ukrainian baristas, roasters, and entrepreneurs are making it all over the world.

The 2014 Russian invasion and the annexation of Crimea provoked an economic crisis; our national currency, thehryvnya, has lost over two-thirds of its value in this time. But for the specialty coffee industry it proved to be a blessing in disguise. “Ukrainians started to consume local products then, be it coffee or whatnot,” Artem Vradiy of Mad Heads Coffee Roasters told me back in 2018. “It was cheaper than importing something [like Italian-style cheap blends]. And so the market figured it would be better to work with local roasters rather than import coffee from Europe.”

The full-scale invasion of Russian forces in 2022 was decidedly bigger, existential threat for Ukraine not to mention its nascent coffee industry. Now it has pushed Ukrainian coffee companies to go global, making strides in the US, Europe and Middle East.

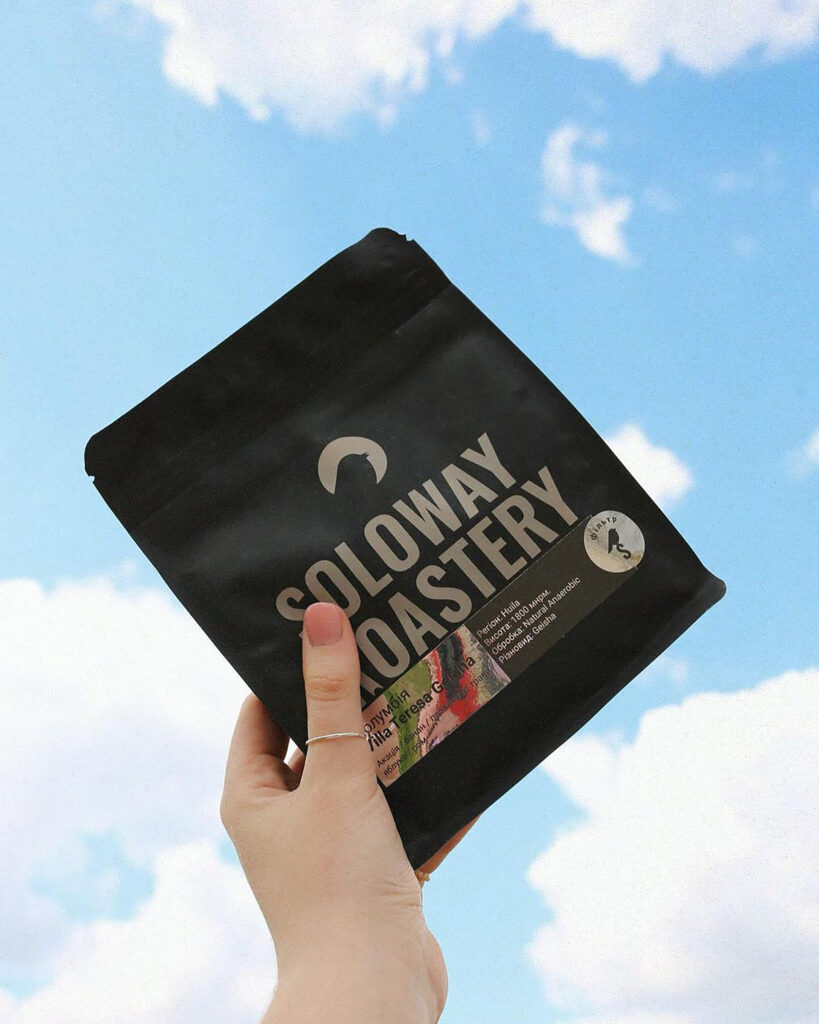

Soloway Coffee, a Ukrainian-owned coffee shop in Chicago, has had a busy first couple of months. Founded in January 2024 by entrepreneurs (and a married couple) Artur Yuzvik and Iryna Yuzvik, the Lincoln Park coffee shop has already established itself on the local coffee scene, took part in SCA Expo 2024 and announced plans to open a second location. Its secret ingredient? Coffee beans roasted back in Ukraine and flown over 5,000 miles to Chicago.

“People go crazy when I say [that Soloway’s coffee is roasted in Ukraine],” Artur Yuzvik told Sprudge. “They just can’t believe it. Like, there’s a note on the coffee bag that it was roasted 10 days ago in Ternopil, and now it’s here in Chicago.” Soloway co-founder points to a number of customers all over the Midwest (including but not limited to the Ukrainian community) flocking to his coffee shop for the famous Ternopil roast. Ternopil is a 200,000 strong regional center in western Ukraine, it’s the base of operations for Soloway Coffee, it’s also the hometown of both Artur and Iryna, who founded the company and its sister coffee shop network Karma Kava back in 2016.

Figuring out the logistics of the whole operation took some time and nerves, Yuzvik admitted. Delivering coffee from Ukraine to the US wasn’t easy in the best of times, it’s all the more complicated now, amidst ongoing conflict. So when the local team of 15 in western Ukraine roasts coffee they then send it across the border to Poland; from Ternopil it gets to Warsaw and eventually, after 6-9 days, to Chicago’s O’Hare airport. “Sometimes we do need to make a connecting flight through Germany, which adds another day or two,” Yuzvik added.

Why go to so much trouble? A combination of factors including cheap labor, expertise, and local pride makes it worthwhile for Soloway Coffee. “I mean, I could’ve started roasting coffee in Chicago. It would definitely be cheaper,” Yuzvik explained. “But that wouldn’t be us. It’s about our product expertise: we’ve been working with our roasting equipment and profiles for nearly a decade, we know it very well. And that’s what makes us stand out.” For Yuzvik, who has lived in the US on and off for seven years now, it’s also about supporting Ukraine in wartime: “I want my company to make money in the States and trickle back to Ukraine’s economy. So we’ll keep roasting great coffee for our Chicago coffee shop in Ternopil.” He added that Soloway Coffee in Chicago employs Ukrainians: 70% of the coffee shop staff either resettled in the US after the full-scale war or have Ukrainian heritage.

A great chance to introduce the American market to Ukrainian roasted coffee presented itself at the SCA Expo, hosted in the city of Chicago in April of 2024, and Yuzvik said his team made the most of it. The Expo organizers visited Soloway prior to the event and proposed an idea to sponsor the Brew Bar at the Cup Tasters competition. “Ukrainian roasted coffee at the world championship—now that’s interesting! Of course we accepted this invitation. It was really great for our team,” he says. Soloway Coffee also hosted a pop-up with Iryna Basko, the 2024 Ukrainian Brewers Cup Champion, who represented the country at the 2024 World Brewers Cup. The 20-year-old barista used the Dotyk dripper in the tournament—a V60 variation that uses authentic Ukrainian clay, which Basko herself co-created. “It’s a great Ukrainian coffee invention, we’re very proud to say that the first batch of Dotyk at our shop has sold out in a matter of weeks,” Yuzvik said.

Yuzvik and his family are now based in the US, yet he still sees Soloway as a Ukrainian company first and foremost. He announces that his family’s second brick-and-mortar place will open up in Chicago this year, though it won’t be coffee-focused. At the same time Soloway is developing another coffee shop in Ternopil. “The Chicago project is very important for us, we’re just getting started here. But I don’t see the American part of our company as a priority. We’re focusing on both Ukraine and the States. It’s all parts of our business,” Yuzvik told Sprudge.

“‘Kavka’ is what my grandmother used to call coffee,” Maks Isakov told Sprudge. The Kavka Coffee founder used a version of the word coffee in Ukrainian language to name his coffee roasting business after moving to the US. Since launching in August 2022 Isakov has opened up its own roastery, expanding available across the state of Maine and launching nationwide delivery.

Kavka Coffee’s is a success story about a refugee coming to the States after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine and starting business from the ground up. When the war came to his homeland Isakov started volunteering with his friends; for instance, he said he was delivering the vital Starlink satellite terminals from Poland. Having sold his coffee shop business in Ukraine, he decided to relocate to the US—Camden, Maine was his first choice because he visited the town in teenage years for work and travel programs.

Isakov’s is also a story of feeling welcomed and supported by the Americans, he hastened to add. “I can’t thank enough all the people that welcomed us. We found nothing but support and understanding here,” the Ukrainian said. Specifically he pays respects to John Ostrand, the founder of Green Tree Coffee & Tea, who helped him with roasting and the general American market expertise. Ostrand also made his roasting equipment available for the first iteration of Kavka Coffee. “We used the Diedrich roaster John was kind enough to lend us up until September 2023. We have our own roastery now, with a 800-square-foot warehouse and an office. But John really did help us at the start and I’m proud to call him a friend even though we have a huge age gap; he has a daughter who’s older than me,” the 28 year-old adds.

A young Ukrainian refugee starting a business in the US—it was a powerful story and it did help to generate some buzz after launch, Isakov confided. “The support we got from the Maine people was amazing. Everyone wanted to support Ukrainian-founded businesses, so they would buy our coffee,” Isakov took a pause. “It can only take you so far though. I was cognizant of the fact that it would be the quality of our work that would define our business in the long term. We do have some clients from the [Ukrainian] community but mostly it’s the Americans who buy our coffee.”

Grateful as he is to the American people, the Kavka Coffee founder is quick to highlight some advantages he has in the Maine market. “Customer service is a cornerstone of our business,” Isakov explained to Sprudge via video call from his roastery. “Ukrainians are hard-working people, we don’t let ourselves relax for a moment. We also have a very competitive market back in Ukraine, which served us well to prepare for new challenges.” The example he provides is a practical one: “I handle all the email correspondence myself, and so a lot of clients get surprised when I reply to them in a matter of hours, not days. I guess you can relax when you have the market cornered but it’s not how we used to do business in Ukraine.”

Another Kavka Coffee advantage, according to its owner, is the back-end team he has back in Ukraine. Isakov works with Ukrainian-based social media marketing, targeting, and video production team, which, he says, is a much more cost-effective solution than the American contractors. He’s also making sure not to overcomplicate things. “We’re not big on these stories about the specific country, region, and altitude of the coffee we roast, we tend to not go into specifics on how it’s grown and roasted. It’s more about simplicity and family-friendly approach, hence the Kavka Coffee name,” Isakov explains.

He says he’s a big fan of blends (“You can experiment with different beans, it never ceases to surprise you!”), and the Kavka Coffee staples use Ukrainian-inspired names. For instance, a blend called Zori—”stars” in Ukrainian—is a dark roast. “This blend is very similar to the night sky with the bright stars—it’s a dark roast with bright flavor,” the Kavka website describes. Another blend called Mriya—”dream in Ukrainian”—is a lighter blend, “perfect to start your day with.” All the blends use only specialty grade Arabica beans, provided mostly by Ostrand’s Green Tree company.

Isakov is adamant it’s his roasting profiles that make his coffee stand out in Maine. “In Ukraine, we’ve got used to lighter roasts over the last decade. But in this part of the US darker roasts are still very much the standard. I’d say Kavka Coffee is right in between a light Scandinavian-style roast and the traditional American one. We don’t smoke-dry the beans, and our roast is lighter and quicker,” he added.

Kavka Coffee is available in all 50 states now, having recently made deliveries to Alaska and Hawaii, Isakov is happy to report. Canada and the UK are also on the map of satisfied clients for his company, also there were some deliveries to Ukraine. “I was surprised by that but I guess it was cool—to send our coffee to the place where it all started for me,” Isakov said. He added that he’s proud of his roots, hence the pledge to donate a dollar from every bag of coffee sold to the Ukrainian cause via Zhytomyr Humanitarian Hub.

Isakov would be the first to admit that he still has a lot of work to do. The roaster he uses now could use an upgrade, he also has a room to grow at the warehouse. For now he is focusing on the roastery but the plan to open up a coffee shop is very much on the table. “I love cafes, and I loved to run brick-and-mortar places back in Ukraine. It’s just that it’s a lot harder to open up and operate a coffee shop in the US,” he says. “For now I’d rather buy a couple of new roasters than invest in a cafe.”

When Artur Yuzvik’s team roasts coffee in Ukraine and sends it to the US, chances are it’s the green coffee provided by !FEST Coffee Mission. The coffee sourcing and trading company is a part of one of the biggest holding groups in Ukraine, which also has a whole array of projects in restaurant business, housing development, education, publishing and fashion. !FEST Coffee Mission Western Ukraine sales manager Vitaliy Petriv has been working with Soloway Coffee for a number of years—as a matter of fact, they were his first clients when he joined the company. “We started with one bag of coffee and now we’re trading tonnes of coffee in this partnership. And then the coffee gets all the way to Chicago!” Petriv told Sprudge.

!FEST Coffee Mission is positioning itself as a Ukrainian trader with global aspirations: it was founded in Lviv but it also has a coffee sourcing hub in El Salvador, a European logistics hub in Poland, and distributing branches in Turkey and United Arab Emirates. The Latin American base of operations was relocated from Nicaragua back in 2022 after Ukraine sanctioned the Russia-supporting Latin American country. The Polish base in Katowice was launched in 2021, marking an opening of a European market for the company, it is soon to be moved to Warsaw in order to optimize the logistical channels. And the recently founded channels in Istanbul and Dubai are starting to make an impact in the Middle East.

Exporting constitutes 20% of the whole trading operation for !FEST. In 2024, the plan is to grow every hub outside Ukraine by 40%. At the time of writing, they are working with 50 clients in the European Union, mostly in Poland, Czech Republic, Romania, and Spain, said !FEST Coffee Mission chief financial officer Veronika Komlach.

Komlach added that the trader sees “great potential” in the Turkey market, exemplified by the plans to open up the second office in the country, in the capital Ankara. “The plan is to grow the share of this market to 20-30% [of our revenue] in the next three years,” she said. They started to work in Turkey with the local sales manager Fahri Ozarslan on February 23, 2022—the day before the full-scale Russo-Ukrainian war started. The UAE-based operation launched in late 2023, with the first green coffee delivery getting to Dubai in February 2024.

What about the United States? The brand is setting sights on the American market, although it will take some time: “It’s a huge and competitive market,” Komlach said. “Our company is looking into it, we have a strategic plan to make an opening there in the next five years.”

Another Ukrainian company heading to the US is Foundation Coffee Roasters, which Sprudge has profiled in a separate feature. It’s one of the most prominent Ukrainian coffee roasters and the roastery behind the 2018 Cezve/Ibrik world championship win for the Ukrainian Slava Babych. (Although it was Artem Vradiy, now with Mad Heads Coffee Roasters, who worked with Babych on the Kenyan variety with a twist of Gesha for the tournament.) Foundation has also opened a shop in Poland before the full-scale Russian invasion started, as well as having a longtime presence in Romania and Moldova. The Poland hub in Wroclaw helps with the logistics and wholesale deliveries all across Europe, and it’s also necessary for the Foundation to establish itself in the EU countries.

“After the big war started we had to take a moment to concentrate on the local team. But now we feel that it’s time to grow and develop other markets,” Foundation chief marketing officer Artem Shvedov told Sprudge. “We’re still a Ukrainian business at heart,” Foundation co-founder and owner Tymur Kozonov added, “and we still consider Ukraine to be our main market. But we have to go west, both because we want to support a number of our team members who had to relocate to Europe and for all the potential that foreign markets bring.”

The next step for the team is the US, the CMO Shvedov claims. The company’s finalizing an agreement with a world-famous Ukrainian restaurant Veselka in New York to bring Ukrainian roasted specialty coffee to America. “Jason [Brichard, the Veselka owner] is a great supporter of the Ukrainian cause. He’s ready to start working with us whenever our American operation launches. We’ve already organized testings with him and the whole team, so hopefully we’ll make it work,” Shvedov said. The plan is to start working with a number of Ukrainian restaurants in the US and use it as a stepping stone to setting up an American hub: “We’ve already found an investor for our expansion in the US, we’re also establishing contacts with the American traders. The plan is to open up a roastery in the States in late 2024 or early 2025. For now we’re focusing on growing the European market, but the US is very much a strategic priority for us.”

The US is a giant market, albeit highly competitive. What can the Ukrainian roasters offer there? For Maks Isakov, it’s all about the quality of service for the Ukrainian roasters: “[The American coffee companies] might think they got it all figured out but we’ll make sure to keep pushing them!”

“Just like in Ukraine for us, it all starts with great service,” Shvedov of Foundation said. “I mean, we’re not the biggest coffee company out there, but we make sure we provide the greatest service. We don’t just supply you with great coffee, it’s a full-circle kind of thing for us. We work with every single client directly, we also provide training and support whenever needed”.

Soloway Coffee co-founder Artur Yuzvik highlighted another opportunity for the Ukrainians in the US coffee community. “It’s mostly teenagers who work in American cafes, and generally it’s a part-time job here. In Ukraine, we do have a lot of people that treat the barista job as a career choice. And the generation of coffee professionals we have now has a lot to offer on the world stage,” Yuzvik said.

“Coffee is an act of service, I believe,” Slava Babych, the 2018 world champion in the Cezve/Ibrik discipline, told Sprudge. The Ukrainian barista has worked for a year at a St. Mary Axe location of the WatchHouse coffee shop chain in London and is now helping launch a new brick-and-mortar cafe called Birdmilk in Notting Hill, serving as head barista. “You can serve the greatest cup of coffee in the world and it wouldn’t be enough,” Babych explained. “It’s the way you talk to the guests, the way you make them feel welcome that makes it special. I think that Ukrainian baristas are among the best in the world, and now we are proving it worldwide.”

Yaroslav Druziuk is the Editor In Chief of Blackfield Coffee, a Ukrainian coffee culture website. Read more Yaroslav Druziuk for Sprudge.