As I pack my bags to leave home in Delhi, India, my mother insists that I carry with me half a kilo of Tata Tea Gold and a kilo of homemade ghee. Protesting against carrying the weight of these two items, which are going to be easily available to purchase in New York City, she argues that I should not have to go searching for a familiar brand of tea when it is going to be something I need to drink the minute I enter my new home.

And I know it’s true. Chai has always been an anchor in my daily routines, giving me a much needed caffeinated push in the middle of the day. As I strive everyday to bring my fragmented self together, chai is a doting companion, reminding me of the sights and smells of my Delhi home.

My chai story is not so different from that of other South Asians who have grown up in the region or in households where preparing and partaking tea is a carefully crafted ritual everyday. Once confined to streetside stalls and South Asian homes, masala chai is now a global mainstay in the culinary world of cocktails, coffee, and desserts. Coffee shop culture in the United States turned chai into “chai tea latte”. My Indian culinary roots want to scoff at this trend, but after having lived in the country for over a couple of years, I do not find myself deriding chai latte. I do not mind consuming it while admitting that although it is not the chai of my taste, it is another spiced beverage that goes well with an alternate choice of milk.

This piece tries to grasp the presence of chai in the United States and how the country’s coffee culture has reshaped it. The study was born out of the desire to explore the trope of authenticity that is often attached to experiencing food cultures. It has also been informed by individuals of South Asian origins who are the spectators of trends around chai and chai latte. I begin my inquiry through a brief outline of the history of tea and chai in India that sets the scene to better understand the remodeling of chai to chai latte and the qualms expressed by South Asian diaspora in the country over this change.

A Brief History of Tea and Chai In India

Tea had been grown in the hills of Assam since at least the 16th century. Located in northeastern India at the foothills of Himalayas and graced by the flow of the Brahmaputra river, local tribes in Assam cultivated tea long before the British set foot in the region. However, the Empire brought its own desire and expertise for growing the crop, which is said to have been hired from China. By the mid-19th century, Assam overtook China as the primary producer and exporter of the crop, as tea had become a common drink among all classes in Britain. Different ways were devised to procure cheap labor and make laborers at tea plantations work as hard as possible.

The tea produced in Assam was meant solely for export to the West. It took time for the beverage to trickle down to the South Asian population, which was used to herb- and spice-based drinks. For a majority of the Indian population, tea was an expensive, foreign habit, another tool of oppression and an object of profit for British rule. It was also a symbol of class, as the highest quality of Assam tea was consumed by the British and Indian elite. A dip in sales after the Great Depression of the 1930s and the potential for making more profits from the Indian population as consumers of tea inspired the British to begin a countrywide marketing campaign to convince Indians to drink tea. Low grade tea was distributed for free and specific directions were given on how it should be brewed. It is interesting to note how such “correct” ways of making a cup of tea were disregarded by locals, who instead preferred to prepare their tea with lots of milk and sugar, the taste of which was appealing to Indians who were used to drinking dairy based beverages.

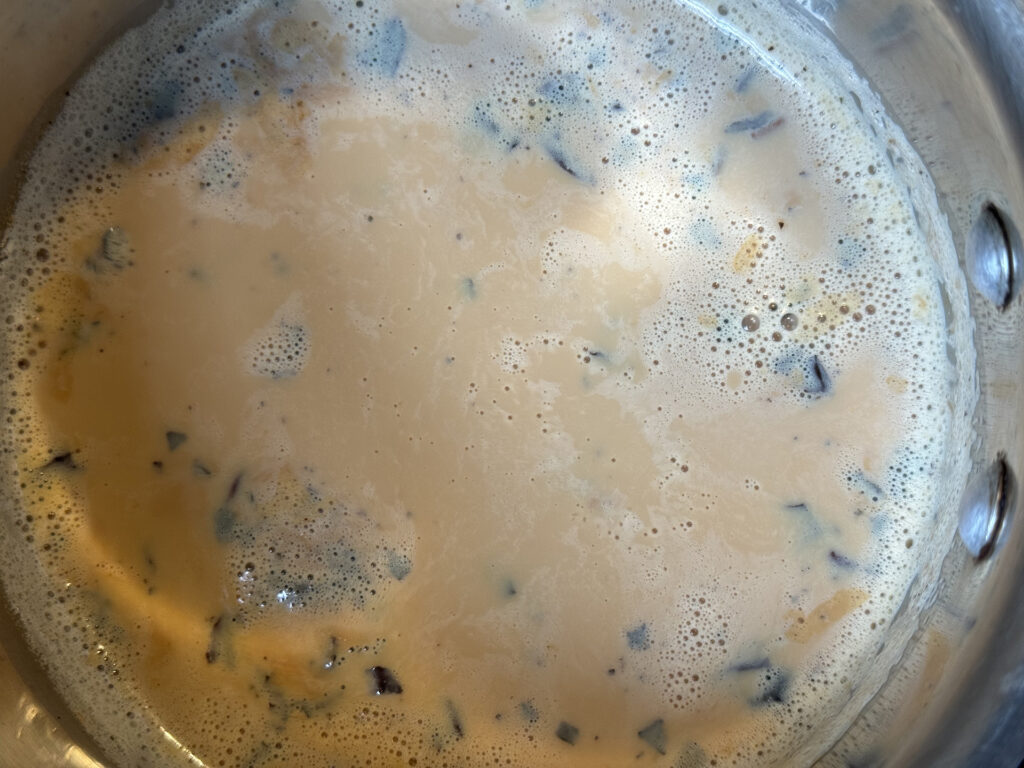

Indians adapted tea brewing methods to create chai. Preparing tea by using the low-grade leaves, water, milk and sugar in a single pot through high heat and letting the mixture simmer for a few minutes for rich taste and thick texture became the preferred method. Spicing the tea made it masala chai as ginger, green cardamom, black pepper, cinnamon, fennel, and cloves along with sugar were added to enrich and complement the taste of the bitter black concoction. At present, not only every culture, region, or household, but even individuals across South Asia and its diaspora are said to have their own recipe for chai. The diverse fragrant spicy cups are telling the histories of families, cultures, and nations. It is through the presence of chai and its chaiwallahs, that South Asians toast to their routine, one small cup at a time.

Chai Versus Chai Latte

The history of chai latte in the west could be traced back roughly to the 1960s when travelers returning from the “hippie trail” brought it back with them. In the 1990s Starbucks launched its own version of a chai latte, which lead to widespread popularity. In a coffee-drinking culture, chai became popular and was claimed as a “healthy” alternative to coffee, given the comparatively smaller amount of caffeine and the medicinal qualities of herbs and spices used in the brew. The market for chai latte has grown since then, with its own place in the menus of coffee shops across the country.

The pitting of chai against chai latte is better understood through the meanings that individuals of South Asian origins attach to their everyday cups of chai. For the purpose of my study, my informants were South Asian food business owners, chefs, and food writers who are directly or indirectly involved in preparing chai, making decisions about its flavor, writing about it, and moreover have shared a nostalgic connection with the beverage.

The South Asian immigrant experience with chai is deeply rooted in the memory of a place and its people. Chai is more than just an everyday beverage, characterized by an emotional and evocative tone that can be traced back to nostalgia and a sense of place. The desire to remember home and their loved ones through the typical recipes of chai is a meaningful way of approaching the past, reinforcing identity, cultural boundaries, and a sense of uniqueness. Making chai over the stove is considered authentic, dynamic, and performative.

In the context of chai, the participants of this study believe that inauthentic versions of chai—such as what is often served as “chai latte”—exist in the market, and it is their responsibility to bring in the real product. They demonstrate what the “original” chai tastes like and adapt it to the framework and convenience of restaurants/delis/coffee shops in the city. They wish to set the peripheries of this authenticity.

As chai latte tries to fit in the category of chai, there is resistance. Since chai is adapted into the cafe culture of America and “latte-ized”, the knowledge of ingredients that goes into its making, techniques, tools, and flavors are used by the immigrant South Asians to assess its originality. However, chai in coffee shop culture has to be adapted for quick service that calls for an instant preparation as opposed to a slow boiling of the mixture over a stove. An iced version has to be an option too in these cafe settings, often accompanied by whipped cream and a sprinkle of spices.

As the participants hold fast to their meanings and versions of chai, they recognize the existence of the form their beloved beverage has acquired due to forces which are well beyond their control. They accept a product of their culture in a foreign market, but the power to make decisions and the ability to display the true flavors of chai is what they demand for themselves.

The metamorphosis of British tea into chai resulted from a visceral and emotional investment into the drink by South Asians, with every region—and every household, and even individuals within those households—fashioning their own highly distinct recipe. While there cannot be only one best way to make chai, there is pushback from members of the South Asian community towards the popular chai recipes and concentrates found throughout America. This is to be expected, and it makes sense. Critique of chai is part of the culture of chai, here as back home, and nobody’s favorite way is the best for another.

As for myself, like nearly all the participants I spoke with, I acknowledge the existence of chai lattes. I even partake in them occasionally in my life in New York. But I still need a homemade cup of chai to ground me everyday as I continue to warm up to the idea of a home away from home.

Navdeep Kaur is a freelance journalist based in New York City. This is Navdeep Kaur’s first feature for Sprudge.